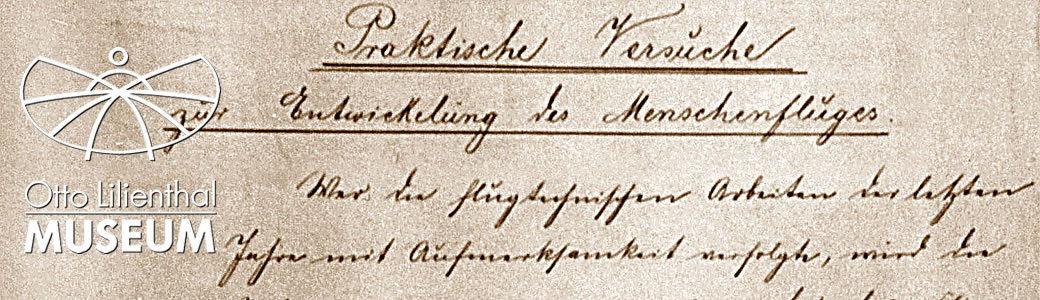

(translated from "Über meine diesjährigen Flugversuche"

Zeitschrift für Luftschiffahrt, 12/1891, p. 286-291)

About my this year's flight attempts

by Otto Lilienthal

It would already be possible to write extensively about the history of the problem of flying, although it seems doubtful to this day how far away we are from finding a satisfactory solution to that extremely challenging physical task. Our nations are competing to see which of them will finally have the honour of delighting humanity with the invention of free flight.

There are diverse methods of getting to the bottom of the secret of flying and equally so are the ways and means in which the inventors and thinkers set about this problem. One looks at the way in which birds fly and tries to derive the rules of flight from it, the other tries to match the exact positions of the wings of flying birds through photographic pictures of the moment in order to try and grasp some of nature's secrets. Whilst some start out with the anatomy of a bird as a basis, from which to derive the necessary conclusions for their flight reproductions, others consider that spreading the knowledge about the rules of atmospheric resistance as the most essential lever in the promotion of the question of flight. The much higher majority of all those inventors limit themselves to theoretical consideration and calculations to show their interest in solving the problem of flight and only few use experiments to illustrate how to fly and to increase experience in it.

In my essay "About theory and practice in free flight" (published in volume 7 and 8 of the magazine) I have already drawn attention to the importance of not only being interested in theoretical calculation but also being occupied with practical flight experiments, which is a productive way of finding out more about the mysteries of air resistance and putting it to our use. I also commented recently on the way in which such experiments could be carried out, as I proved that a form of free flight exists which human beings can carry out themselves with the means which he already has to his disposal, a flight which merely needs a simple apparatus to put it into practice and can be done so perfectly safely. It is the flight over a downward facing slope, in which one can make use of a relatively motionless apparatus which looks like the outspread wings of a bird. The jumping height should not be too high at first, so that there is no danger during the jump or flight and can be increased with experience and success rate. In this way I had developed a complete program to gradually perfect the flight attempts and make a definite picture of how far complete free flight can be achieved.

Soaring flight, which, in its most perfect form, must surely be the most worthwhile goal of any aviator, gives us therefore the first and most comfortable opportunity of performing free flight albeit in a limited form. Soaring flight or gliding is flying without wing beats and continuous soaring flight is the ideal of all flights. The natural flight of many kinds of birds shows us in the most awesome way, that this is indeed a possibility..

The most distinguished task of any aviator is to get to the bottom of the secret of flight. True soaring flight requires no special motoric achievement, so the hesitation one may have had about lighter and stronger motors is not necessary. The only 'motor' that is necessary for soaring flight is the wind itself. I have proven that the wind often has a strong, uplifting direction so that when using the properly curved wings the power and the direction of the wind itself is enough to achieve constant flight without wing beats.

When trying to copy this type of soaring flight, which is fully dependent on the quality of the wind, it is not very useful to sit around brooding or being theoretical. The quality of the wind and the most advantageous forms of wings have to be studied in a practical way. We must try to get a feeling for it, all our senses have to learn to recognise the dynamic factors of the air and the wind and put them into use.

Convinced that practice and experience will do their part, as they do in all forms of human ability, I made numerous practical flying attempts last summer according to the points I have already mentioned.

The apparatus I made use of looked like the outspread wings of a bird. The wing profile was in a concave form and had an arrow height, which was a tenth of the width at every given point. It was reckoned on that the arrow height would bend during flight sinking to a twelfth of the width or even lower. The wings were so stiff, however, that they did not bend. As a result they weren't very advantageous in strong winds, which according to our former experience would need a smaller bend in the wings.

At the beginning the flight surface was 10 square metres but was gradually reduced after numerous changes and repairs to 8 square metres. The wing span of the new apparatus was 7,5m with the largest width being 2m. The wings ended in two sloping tips which were turned backwards. The frame of the wings was made of willow but so that the two stronger rods led towards the tips and weaker rods ran crosswise. The cover of the frame consisted of shirting with a varnished coating. The weight of the apparatus was about 18kg.

To hold on to the apparatus you put your lower arms into two padded notches on the frame while you clasp two corresponding grips at the same time. Through this you had the absolute control over the apparatus and you could safely support yourself with your arms but it was also possible to release the apparatus in dangerous situations or to get yourself out of it. At first I had a springboard erected on a big lawn in my garden which I could alter in height and from which I could practise jumps. At the beginning the height was one metre and I extended it to two metres. There was a run of about eight metres. Without much practice at all it was possible to hold the wings during the jump so that the buoyancy was at its maximum. The result of this attempt was a 6 to 7 metre jump at a height of 2 metres, during which one felt as if one's body was hovering in the air with its weight on the apparatus. The touchdown on the soft ground was not so bad, and therefore one can practise the jump 50 or 60 times without coming to any harm. Still, it has to be said that these jumps were carried out in an area of my garden which was protected from the winds by trees.

After having practised handling the apparatus in this way for several weeks I changed my place of practice to Werder and Grosskreuz, where I could practise different jumps from different heights in the open. I realised immediately that the stronger winds had to be very much taken into consideration. These flight attempts required positioning the apparatus against the wind at all times. It is even necessary to adjust the apparatus so that it can adapt itself to the wind, because if the apparatus goes off course in the wind and one side has considerably more wind pressure than the other, it is almost impossible to correct the course. The automatic setting of the apparatus against the wind was achieved by the addition of a vertical steering area.

I have carried out the jump from a bigger height a thousand times on the practice terrain mentioned above, during winds of various strengths and speeds which has all added to my experience. If the wind has a strength of more than 5 - 6 metres the handling of the apparatus is extremely difficult and before you have achieved a certain amount of skill in the matter you shouldn't try to lift your feet from the ground. A number of times I was lifted up several metres away from the ground by some unexpectedly strong wind and was only able to prevent a crash in the overturning apparatus by getting myself out of it in time. It is extremely important to chose the correct angle of the wings which will face the gusts of wind. Aiming them too upright you will only be pushed back by the wind and won't be able to move forward at all. But if you aim the front edge of the wing even just a little too low, the wind pushes down onto the area from above and a crash is then unavoidable. It takes a great deal of practice until you have reached a point where it is no longer dangerous to jump from a height in strong winds. But when you have achieved this, which can be made easier by a-fixing a horizontal tail wing, it is possible to do some very interesting and instructive exercises with this wing-like apparatus. The final result on this practice area was that it was possible to carry out a jump of 20-25 metres from a jumping height of 5-6 metres in calm as well as stronger winds.

There was only one difference in the duration of the flight. The stronger the wind the longer you stayed in the air.

In moderate winds you could modify the movement through the air by inclining the wings more or less to move up and down in the air, making an artificial wave-like movement. I noticed no advantages of performing a wave-like flight of this type, although it has been praised by other aviators. I merely carried out this type of flight to practise the random influence of flight and to raise the quality of safety in handling the apparatus. During such flights the weight of the body is carried completely by the apparatus, that means that whilst you fly you get a feeling of complete security.

Shortly before landing you have to lift up the wings at the front to reduce speed so that the landing is not too bumpy and you don't topple over. This applies to jumps when the wind is calm. When you fly against the wind, however the landing is always a gentle one. Of course, a gentle landing requires practice.

The quality of the ground has a considerable influence on these experiments. As I already said the movements are always made against the wind. A jump from a steep slope is considerably different to one from a gently sloping one. Before a steep drop the wind is in more of a whirl and on the edge of a drop the wind often moves in a steep upwards direction. If you take a run after the edge of the slope with the wings in a too horizontal position you get caught up in the upward moving windstream, which is noticeable at once, and often results in suddenly being lifted up several meters when there is a strong wind. Once it even happened that I was lifted up by the wind and when the wind suddenly became stronger I was thrown back to the slope although I had already moved several meters away from it. At the same time it also once happened that I almost came to a standstill in the middle of the air due to the sudden increase in the strength of the wind.

The speed of the wind at the foot of a steep slope is much slower than at the top and so jumping from steep slopes is not as advantageous as from gently sloping ones. On the latter the wind tends to move upwards at a more constant speed and strength so that you can use the lifting effect of the wind up to the place where you land. To achieve the longest jumps and longest flight duration it is best if the wind is reasonably calm during the run-up and the jump itself and strengthens gradually during the flight.

The training area we used was not suitable for larger distances nor larger starting heights. That's why I'm forced to look for another area from which to continue these attempts and in order to practise the jump from an increased height and fly longer distances.

At least we could conclude from the previous attempts that the flight slanting down vertically can be carried out with a very simple apparatus and that it can be practised quite safely from a number of different heights.

Some of the alterations which I made to the apparatus in the duration of the practice taught me that in creating the shapes of the wings it is necessary to look for the crucial point of their usefulness. I also learned what sort of improvements would increase the stability and the weight-bearing capacity of the wings. I can't, however, go into this in further detail until I have continued and completed my attempts in this field.

(translated by a group of final year pupils as a project at the Lilienthal Grammar School)