(copyright G. Henderson, 2006, with friendly permission)

Fly Like a Bird

The Dickenson Wing Story

By Graeme Henderson / Australia

2018 - 55th Anniversary of the first fight of the modern day hang glider,

designed by John Dickenson

Eclipsed by the size of the sport that he founded, John Dickenson's story has remained a mystery in spite of the many efforts over the years to highlight his eminent role. Myths abound, credit has gone to people who have no true claim to it, and Australia's greatest contribution to global aviation has continually been overlooked. As the absolute founder of the sport John Dickenson deserves better than this.

John Dickenson, aged 44

In the spring of 1963 an Australian, Mr John Dickenson, built the aircraft that evolved into the modern Hang Gliders built today. Often mistakenly called 'The Rogallo Wing', it should correctly be called 'The Dickenson Wing'. It is important to note that Dr Francis M. Rogallo played only a small part in the building of this aircraft, no more than say Otto Lilienthal, or The Wright Brothers, or even Leonardo Da Vinci.

John Dickenson passed away on the 5th of July, 2023. He was 89.

This 2006 model, competition Hang glider is a direct descendant of the Mark I Dickenson Wing.

This 2006 model, competition Hang glider is a direct descendant of the Mark I Dickenson Wing.

As a young boy growing up on the Northern Beaches of Sydney, John had been fascinated by flying things. He often watched seagulls soar at Flat Rock, he built and flew model aircraft, and he was particularly attracted to minimum structured flying machines.

This early study of aviation, although informal, was a vital ingredient in the quite amazing development of 'The Dickenson Wing': This story is testimony to the old saying that success happens when preparation meets opportunity.

John Dickenson flying his Auto Gyro

John Dickenson flying his Auto Gyro

John became an Electronics dip. Engineer. In 1955 he married Amy Holmes-Prinold and they moved to Grafton in 1960. He began playing around with Auto Gyros, even designing parts of the spar for his rotor blades. These were machined by Mr Pat Crowe. Pat will appear again as the boat driver when we get to the first flight story. In early 1963 one of the members of the Grafton Water Ski Club who had been towing John along the beach in the Auto Gyro, mentioned this back at the club. John was a water skier and a club member.

A water ski kite. Although John couldn't get one to work

A water ski kite. Although John couldn't get one to work

Water Ski Kites had been around for a while, and since John was obviously not afraid of flying the club asked him to build and to fly, a Water Ski Kite as part of the club's contribution to the Jacaranda Festival. John agreed to give it a go and set about building models. He had no plans, only descriptions of ski kites to go on. John tried a few kite designs and all of them seemed to be fine until he suspended a weight beneath them, at which point they all developed a strong propensity for locking into a screaming dive that only the ground could stop.

A vertical wing is a sail. A horizontal sail is a wing

A vertical wing is a sail. A horizontal sail is a wing

As John worked on this, he started to hear the stories of the attempts by people to fly these kites at previous festivals, 'The Kite Stunt', it seemed, was a real crowd puller. John learned that some of the previous attempts had resulted in stunning crashes, the impact of which was dampened somewhat by the water, but were none the less severe. Not wanting to be yet another casualty, John set out to build a glider based on the wing of the Flying Foxes - large fruit eating bats with a wing span of about 1.3 metres - that are abundant in the Northern Rivers of N.S.W.

bottom view of flying fox

bottom view of flying fox

John built models and they flew really well with a good glide angle. The problems were the complexity and the expense involved to build one, and also, he had no control system! It was while working on these problems that a member of the water ski club showed John a photo of the Flexible Gliding Parachute, designed for N.A.S.A. by Dr F.M.Rogallo. Dr Rogallo was interested in flexible wings and self-inflating pneumatic structures. Borrowing on sail designs, he had removed the mast and spars, and using two triangular sails he built a 'Rogallo Wing'.

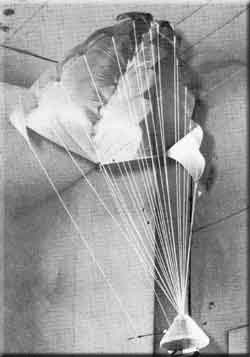

The photo of the Rogallo wing shown to John Dickenson

The photo of the Rogallo wing shown to John Dickenson

John took the two triangular sails and put the mast (crossbar) and spars, (leading edges and keel) back in. He built a model based on the photo and to his surprise its glide angle was just as good as the much more complex 'Bat Wing' models. At this point in time John's motivation was to keep his word to the club members and to fly something at the Jacaranda Festival. Hopefully something safer than the kites he had already built.

The simplicity of the Triangular sails consigned the 'Bat Wings' to history. But John still had a problem as did the others around the country and around the world, who unbeknown to John, were working with similar wings. In particular were two blokes in Sydney, Dick Swinbourne and Mike Burns, whose company Aerostructures had begun designing weight shift control "Skiplanes" in 1962. They were a Delta Wing on floats, that used a mechanical weight shift system controlled by a 'joy stick'. Dick and Mike had obtained information from N.A.S.A, and were qualified Aeronautical Engineers. They will join the story again later.

Apart from Aerostructures, everyone else's problem was this: how do you control these aircraft? Hanging by ones armpits between two parallel bars and swinging ones legs about was a common practice, but it was inefficient from a control point of view, and inherently dangerous. The rule was simple: 'Don't fly higher than you are prepared to fall'.

One afternoon John took his daughter to a nearby park and while swinging his daughter on the swing, his mind continued to churn on the problem of controlling the wing. It had to be simple, time was slipping by, and a nasty dive into the Clarence River on a kite was looming.

"Swing me sideways Daddy", said Helen, "Swing me sideways".

"Uh, what?" says her not so attentive father.

"Swing me sideways!"

John swung Helen sideways and 'Eureka!' it was so simple! Hang on a swinging seat beneath the wing, and have something to swing against. The rest was simple mathematics and experimentation.

John Dickenson about to test the half scale model. 1963

John Dickenson about to test the half scale model. 1963

Starting with small models, John made some basic calculations to work out the wings optimum size and then, through physical testing and more calculations he set about building a half size model. This was towed behind a boat and it allowed John to test his control system. With the control system apparently working John set about getting the materials to build the full sized Glider. His budget was tiny. In the end the materials cost a mere twelve pounds - twenty four dollars. The chosen and tested membrane was a length of blue plastic tube that when cut to lengths was normally used to cover bunches of Bananas to protect them from birds and sun damage. John cut the tubes open and laying them out with some overlap, he fixed both sides with ½ inch blue plastic electrical tape. The keel and leading edges were one and a half inch square, clear, Oregon, i.e., straight grained, with no knots, or flaws. The wood was carefully selected with two lengths of equal weight chosen for the leading edges, and the next best one for the keel.

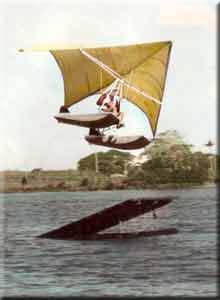

Rod Fuller skiing with the Mark I, 1963

Rod Fuller skiing with the Mark I, 1963

The cross bar was a length of T.V. antenna aluminium, with a length of turned wood jammed into it to give it the required strength. If you look closely at the first glider, the cross bar is well forward of the pilot. This was due to its length restrictions - in later models the cross bar went back to the top of the A-Frame.

The plastic wrapped around the leading edges and was attached with a length of 'D Section' wood and nails. Clothesline wire cable was used for the bracing wires, and seat belt webbing was used to make the seat.

All was ready and on Sept 8 th 1963 the crew assembled at the Grafton Water Ski Club to give it a go. John went first but between centre of gravity issues and inexperience, he was unable to get off the water. Exhausted he handed the task to Norm Stanford, who also was unable to get into the air. The next brave soul, Bob Clements, went up briefly, came down quickly and never tried again. Next came a man not to be trifled with - Rod Fuller, club water ski champ and dare devil, he would go on to be a founding member of the Grafton Gliding Club and become a respected member of the Gliding Fraternity. On this day Rod got to hold every hang gliding record in the book, and he became the first person to experience the feeling of flying a Dickenson Wing.

Pat Crowe was driving the boat; He and Rod had agreed on their signals- if Rod nodded his head Pat was to go faster; if Rod shook his head Pat was to slow the boat. The wind was from the South, about 45 degrees to the river bank, so they had decided to head out into the river and then to turn into the wind before they would have a go at flying. Once they were headed into the wind Rod nodded his head, Pat opened the throttle, Rod lifted the nose slightly and shot straight to the top of the rope, 140 feet off the water and nearly right above the boat!

These blokes had no idea about wind gradients. Pat looked up to see Rod shaking his head furiously. Pat however could not slow the boat too much, as at 18 mph the boat would drop off 'the plane' and virtually stop dead in the water. Pat had great concerns for his mate as no-one knew what would happen if he just stopped. Pat was worried that Rod would overfly the boat and be slammed into the water ahead of him.

Rod was still getting over his initial terror. The centre of gravity was a little far back, and while going up was easy he had no way to get down. After a few seconds, Rod calmed down enough to start taking in the view and then he looked up at the Banana Plastic and electrical tape sail. There was only the slightest ripple and no obvious strain on the plastic. He quickly gained confidence in the controls, there was plenty of feedback and he had plenty of roll control.

John Dickenson flying the Mark III, Grafton 1965

John Dickenson flying the Mark III, Grafton 1965

All was going well and they would have kept going down the river until they figured out how to get Rod down safely, but when Pat looked ahead he realised that the Grafton bridge meant that was not an option. They were only seeing if the wing would fly and having discovered that it would, some of the inadequacies of their briefing became apparent. There had been no thought given to this stage of the affair and Pat was alone and worried. Rod was much higher than the bridge so Pat began a long, gentle turn using every inch of the river. At the top of the rope Rod was right over the bridge, and as Pat just skimmed the far bank, Rod was flying over the buildings on the bank.

The Aerostructures Skiplane

The Aerostructures Skiplane

Now that they were travelling with the wind, the wing began to lose airspeed and altitude. Rod returned to the water and skied back towards the clubhouse before being upended into the river by the tail wind. The ultimate flying machine had been built, and flown!

After some fine-tuning, John was the next to fly, and he was amazed at the effectiveness of the control system and the feeling of security that the wing gave, in spite of its flimsy appearance. John had built the wing for a stunt; it was intended to do some practice runs and to be flown for the Jacaranda Festival then to be thrown away. Flying his wing for the first time, John started to see that what he had built was a lot more significant than a one-stunt toy. That wing flew at the festival and for many months afterwards before the wood was broken up to fuel a barbeque on Australia Day. By then of course Mark II was built, and found to have problems with durability. It had an all aluminium frame, and John had stuck the sail to the leading edge with contact adhesive. After a couple of flights the material started to delaminate from the tubing. Instantly the Mark II glider was abandoned.

Amy sewed the yellow nylon sail for the second Mark III, (the first Mark III had banana plastic). This glider had an all aluminium frame, battens and a scalloped cut to reduce sail flutter at the trailing edge.

Mark IV followed, Duraluminium frame, Terylene sail, stainless steel bolts and cables, and easily foldable for transporting.

Rod and John flew often for the next two years until John moved back to Sydney, where he eventually met Mike Burns. Mike's company, Aerostructures began making Gliders using John's design in a deal with John. Aerostructures took John Dickenson's backyard project, and applied professional aircraft standards to it. This put the future of the aircraft type, hang gliding and micro-lighting, on a sound footing. There was a 100% safety record with all of these wings up until this time.

The next major breakthrough for the sport was when Bill Moyes and Bill Bennett, were taught to fly the glider by John and Mike. They bought gliders from Aerostructures , and took John's wing to the world. John continued to collaborate with Bill Moyes for the next few years, helping Bill in his quest to improve the performance of the wing. The rest, as they say, is history. In a modern hang glider you will find many refinements but you can still see the basic features John Dickenson built in Grafton.

Amy Dickenson carries a folded Mark IV in one hand, 1965

Amy Dickenson carries a folded Mark IV in one hand, 1965

In September 1963, a whole new type of aircraft was invented - its simplicity is beautiful. John Dickenson invented it, and built it with only the simplest of tools. Rod Fuller - strong, quiet, champion water skier, and pilot at heart - flew it and proved its worth. Pat Crowe kept his head and dealt with the problem of; 'What do we do if it works?'.

John Dickenson lands after breaking the endurance record. 1969

John Dickenson lands after breaking the endurance record. 1969

Times have changed, Health and Safety issues have removed the swings from the park where Helen inspired her father. It required the right place, the right man, and the right time. It took all of these people mentioned, plus the generosity of the other members of the water ski club. They didn't have to let these bird men fly and take up precious water skiing time. It took the mighty Clarence River, wide enough to allow them to avoid wrapping Rod around the bridge. There was no release for the first attempts, and the two 70 foot long ski ropes had no weak link.

One of the Drawings sent by John Dickenson to Dr F.M.Rogallo, after Dr Rogallo wrote to John Dickenson asking for details about Johns' glider. 24 th November

One of the Drawings sent by John Dickenson to Dr F.M.Rogallo, after Dr Rogallo wrote to John Dickenson asking for details about Johns' glider. 24 th November

If you were to take John's design back in time, it could have been built 5000 years or more ago, light linen or silk, would make perfect sail material, light weight timbers were available or Bamboo, strong ropes would have done the rest. Leonardo Da Vinci could have built a 'Dickenson Wing' as could Otto Lilienthal. This simplest of all aircraft remained hidden from all but one man. His basic maths and lack of formal training allowed him to think outside the box. His experience with flexible bat wings and his childhood fascination with building minimum structured model aircraft, plus a photo of Rogallo's gliding parachute and his daughter's request to be swung sideways, was all it took. Not much. Just preparation meeting opportunity.

Grafton and John Dickenson's gift to the world is one of the purest forms of flying machine known to man, a wing by itself, not the poor relation of the other types of aircraft. 'The Dickenson Wing' has evolved into the ultimate flying machine, today's slick, fast and safe hang gliders. The way to appreciate that is to learn to fly one, and live man's age old dream to soar like a bird.

Rod Fuller and John Dickenson with the finished replica, 7 sept, 2006

Rod Fuller and John Dickenson with the finished replica, 7 sept, 2006

On the 28 th of October 2006, the Clarence Valley Council will unveil a Memorial to mark this event. Hang Gliders will be included as part of the South Grafton Aero Club's Annual Muster and a part of the Jacaranda Festival Parade. A replica of the original glider has been built and it ground handled perfectly, under our agreement this glider will not be flown. The Northern Rivers Hang Gliding and Paragliding Club will be having an aero-tow fly-in at the South Grafton Aero Club. Bill Moyes is bringing one of the Aerostructures Mark IV gliders, plus a boat and a winch, to be flown from the site of the first flight. Pilots and Aircraft of all types are welcome to attend.

For more information email Greame.

Note: Regretfully Amy Dickenson passed away in January 2002, after a long battle with breast cancer.