translation from: "Erfunden - Vergessen - Bewahrt? - Bedeutende Erfindungen aus Mecklenburg und Vorpommern", Rostock, 2000

"The Other Lilienthal"

the multi-faceted life of Gustav Lilienthal (1849 — 1933) - the younger brother of Otto Lilienthal

Bernd Lukasch / translation: Beau Griffith

When one talks about Gustav Lilienthal, you emphasize his first name, to make it clear, "No, I don't mean Otto." The younger brother of the world-renowned aviation pioneer remains until this day obscured in the shadows of his older brother's fame. Born on October 9, 1849, in Anklam, only a year younger than his brother Otto, Gustav outlived him by almost forty years. His gravesite, like his brother's, is honored as a landmark by the city of Berlin.

When one talks about Gustav Lilienthal, you emphasize his first name, to make it clear, "No, I don't mean Otto." The younger brother of the world-renowned aviation pioneer remains until this day obscured in the shadows of his older brother's fame. Born on October 9, 1849, in Anklam, only a year younger than his brother Otto, Gustav outlived him by almost forty years. His gravesite, like his brother's, is honored as a landmark by the city of Berlin.

He died on February 1, 1933, at the age of 83, on his way to Berlin's Airport "Johannisthal", in the midst of the work which had totally dominated the last years of his life. Even at his advanced age, Gustav Lilienthal carried forward the work on bird-like flight for humans which he and his brother had begun together in their youth — an undertaking whose development, in the opinion of Gustav Lilienthal, had veered in the wrong direction following Otto Lilienthal's death in 1896. And so the octogenarian worked away on his giant wing-flapping aircraft, which never even left the ground, at the Berlin airfields Adlerhof and Tempelhof (which had in the meantime become major urban airports). So, was Gustav's biography merely a tragi-comedy lived out in the shadow of his famous brother Otto?

Gustav Lilienthal's flapping-wing aircraft, with 3 horse-power motor at Berlin's Tempelhof Airport, around 1927

Gustav Lilienthal's flapping-wing aircraft, with 3 horse-power motor at Berlin's Tempelhof Airport, around 1927

Gustav Lilienthal's private papers and book collection are preserved principally in the archives of the city of Berlin. They document his wide-ranging writings, and include a collection of diagrams mounted on cards that accompanied his numerous lectures on the subject of flight technology. In Berlin's German Technology Museum (Deutsches Technikmuseum) an artificial bird can be seen which he used in his experiments. The Otto Lilienthal Museum in Anklam displays the main wing spars of the "great bird" with a wing-span of 17,5 meters, which is a surviving example of work conducted at the research station at Altwarp, on the Stettiner Haff (directed by Gustav Lilienthal beginning in 1914).

Much more extensive is his legacy in other fields: villas, suburban homes and pre-fabricated buildings in and around Berlin, pattern books developed for his Arts and Crafts school, toy patents and finally projects he initiated to reform society, which are actively pursuing their original missions even into the present day. That Gustav Lilienthal was in the past principally seen as the 'other flight pioneer', may well be due to the work he pursued in his eighties, surrounded by the aura of the then already world-renown Lilienthal name, and by the great number of published works documenting his and his brother's flight research that he wrote beginning in 1920.

Gustav Lilienthal's other earlier fields of endeavor were scarely publicized by him, even though the concrete signs of his influence which continue to be visible even today stem mainly from his professional activity as a home builder: suburban homes in Berlin Lichterfelde considered remarkable even by contemporary standards; the simple, practical housing developments at the cooperative "Freie Scholle" (Free Soil) in northern Berlin; or the homes of the "Eden" fruit growers cooperative. In the "Freie Scholle" a memorial stands today commemorating him not as a builder or a flight pioneer, but rather as the founder, and for many years chairman of the cooperative.

Gustav Lilienthal's other earlier fields of endeavor were scarely publicized by him, even though the concrete signs of his influence which continue to be visible even today stem mainly from his professional activity as a home builder: suburban homes in Berlin Lichterfelde considered remarkable even by contemporary standards; the simple, practical housing developments at the cooperative "Freie Scholle" (Free Soil) in northern Berlin; or the homes of the "Eden" fruit growers cooperative. In the "Freie Scholle" a memorial stands today commemorating him not as a builder or a flight pioneer, but rather as the founder, and for many years chairman of the cooperative.

The "Eden" cooperative (whose name signifies its' members intent to create a paradise through the reform of one's life and applying the principles of the "Free Land" movement in a real world environment) continues to exist even to the present day. And then there are the more ephemeral construction projects which take place in children's playrooms: before toy-makers manufactured their blocks from plastic, "Anchor Stone Building Blocks" ruled the world of toy building blocks. These and a great number of other building blocks and other toy building systems date back to Gustav Lilienthal's inventions. Some of them are even patented under the name of his brother Otto.

>>> Lilienthal and his stone building blocks: the story (German)

Housing Reform — Social Reform — Life Reform

Where do we begin in attempting to describe Gustav Lilienthal's life? How do we weigh the merits of his Arts and Crafts School against the "Eden" fruit growers cooperative; The homeless shelters in "Lobetal" compared to his flapping-wing aircraft and the "Castles of Lichterfelde," with it's english tudor style suburban villas complete with towers and battlements. The staff of the museum pondered these questions as they prepared an exhibition in 1999 commemorating the 150th birthday of Gustav Lilienthal. How were we to make sense of such a varied biography as his in an exhibition? What kind of a theme would we be able to discern that wouldn't just be a chronological listing of his accomplishments?

The term "free", which is often mis-used today, is what first led us in a promising direction: while visiting the still-extant "Eden" fruit growers cooperative in Oranienburg (near Berlin) we drove along a street named "Freilandweg" (Free Land Way). "Freie Scholle" (Free Soil) was the name of the home building cooperative that Gustav Lilienthal founded in 1895 ... flying, free as a bird. "He was a free and humane world citizen, as were his colleagues" we recollected from the memoirs of one of his colleagues.

We discovered the kind of freedom he had been laboring for almost by accident, in the autobiography of Franz Oppenheimer (1864-1943). Oppenheimer became in 1919 the first Sociology professor in Germany. Before that he was editor-in-chief of "Welt am Sonntag" and later a professor in Palestine, Japan and the USA and founder of the "American Journal of Economics and Sociology." He wrote: "I was a convinced socialist regarding it's goals. But I was not convinced by Social Democratic, Marxist solutions to the problem ... to me, in any event, the concept of this 'future state', that would control it's citizen from a central bureaucracy throughout the course of their entire lives, was contrary to my deepest convictions, and I sought after another solution ... . (Theodor) Hertzka had famously sketched out a mental picture of a new form of socialism in his novel "Freiland" (Free Land), which challenged the authoritarian socialism of the Marxists; a society in which equality is achieved without renouncing economic and political freedom was portrayed. All over Germany and Austria groups of young people had formed, who were determined to live out these ideals ... in addition, even the co-inventor of the first aircraft, Gustav Lilienthal (brother of Otto Lilienthal), for example, belonged to this group of "Freiländer", as they called themselves, and Otto himself appeared with less frequency at their meetings."

(Franz Oppenheimer: "Mein wissenschaftlicher Weg" , in Felix Meiner (Hg.): "Die Volkswirtschaftslehre der Gegenwart in Selbstdarstellung", Band 2, Leipzig 1929, S. 82)

Another significant clue can be found in Gustav Lilienthal's "Free Soil." The first street in the housing cooperative was named "Egidy Street" by the residents. Egidy's name is well-known to us as having been a correspondent of Otto Lilienthal's. In one of his letters to Egidy, Otto elucidates his vision of human connectedness and the peace-fostering effects resulting from the invention of the aircraft. Moritz von Egidy (1847-1898) had as a promising young officer from Saxony in his essay "Ernste Gedanken" (Serious Thoughts) sounded a call to action for a reformed Christianity. His socio-ethical essay, to a certain extent a Christian response to the wide-ranging public dissatisfaction with conditions at that time, brought him, to his total surprise, the attraction of a gigantic following from various political circles, and life-long surveillance by the secret police. He died in 1898, following a speaking tour that he cut short due to illness — though unfortunately not soon enough. One of the many memorial services at the time of his death took place on January 29, 1899 in the Concerthaus on the Leipziger Strasse in Berlin. A poster announcing the meeting has survived. The "Committee of the Memorial Service" contains a long list of names, and Gustav Lilienthal is among them. Besides him, other well-known figures are listed, such as: Wilhelm Liebknecht, as well as Franz Oppenheimer, Baroness Berta von Suttner, the land reformer Adolf Damaschke and the anarchist Gustav Landauer, or Prof. Wilhelm Foerster, an astronomer, Board Chairman of both the "Urania" a science for the layman society in Berlin and of the "Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ethische Kultur" (The German Society for Ethical Culture) the atheistic counterpart to the Egidy Society.

We had been seeking for ideas among Gustav's construction innovations, flight technology research, arts and crafts school, and toy inventions, and had coincidentally discovered something completely different, as a fitting theme to sum up the life of Gustav Lilienthal, namely: his involvement in the reform movement at the turn of the 20th century. It was a broad and multi-faceted response to the emerging consequences of those 'new times': the coming home to roost of unresolved societal problems; the effects of industrialization, urbanization and depletion of the environment; and reform movements such as: land reform and vegetarians, or peace movements, or anti-alcohol campaigns, or education reform, or nudist colonies, or the Jugendstil (Art Nouveau); the garden city movement, the cooperative movement, prevention of animal cruelty, social ethics and Naturopathy, or socialism and pacificism, feminist movements, economic reform and environmental conservation. Today many of these ideas are naturally found in political platforms, such as environmentalism, liberalism, the struggle for equal rights for all, and the social welfare state. Other movements, which are unjustly mostly forgotten are: Freiland (free land), Freigeld and Freiwirtschaft (free economy).

This was the common spirit that united the Lilienthal brothers, which is reflected in their otherwise vastly different projects and careers paths. When he wrote about himself, and his fundamentally distinct brother Gustav in 1894, whose life trajectory was so different from his own, Otto opined: "my brother was and is my second self." They shared the view that technical progress that didn't concurrently seek social and societal progress and the realization of human potential at all levels of society, didn't deserve to be called progress.

Today, at the turn of the 21st century, Gustav's reform ideas and projects appear surprising and naive, yet vaguely contemporary and up-to-date. The past century was one of gigantic technological advancement, along with the unrestrained use and abuse of the fruits of this progress. The 20th century became the century of the airplane, the exploration of space, the harnessing of the atom and artificial intelligence, but also the century of Auschwitz, Hiroshima and Chernobyl. Failed comprehensive societal solutions stand alongside ever more limited social progress. The lived ideals at "Eden" and "Freie Scholle" have not changed the world, but they have proudly outlived all the historical challenges of the 20th century. Appearing on this bridge to the present are the details of the life of Gustav Lilienthal which are most worth recounting. In 1992, Rudolf Bahro (critic of the former German Democratic Republic as well as the Federal Republic of Germany) wrote: "the way our contemporary cultural model is set up is as follows: from the bottom up, and coursing through nearly all of society's institutional permutations, we never feel satiated. This inevitably disturbs the natural equilibrium and hinders the further unfolding of human potential. In any event it calls for a new paradigm for living. Bahro draws the conclusion that state investment in alternative projects for societal restructuring would be substantially more meaningful than the billions invested in scientific and technological innovation.

The Arts and Crafts School

The cloth trader Gustav Lilienthal of Anklam fathered 8 children. Five of the children died within their first year. Gustav is 11 and his brother Otto is 12 when their father dies. Gustav then transferred from a college preparatory high school into the Anklam trades school. After graduating, he apprenticed as a mason, and subsequently as a journeyman masoner. Meanwhile, with financial help from relatives, Otto had begun his studies at the Berlin Crafts Academy and eventually brought his brother to live with him in Berlin. Gustav applied to the Berlin Building Academy in 1869. He left there in 1870 and worked in Prague and in London, where he joined the "Royal Aeronautical Society" of Great Britain. Following his return, he worked for Berlin's building administration. It is clear it was the artistic and creative side of the building profession that had interested him. In 1877, he left his obviously unloved post so as to pursue a career as an artist and art teacher. He founded the "Institut für Kunstgewerbe und Kunststickerei" (Institute for Arts, Crafts and Embroidery), worked for the "Schule der weiblichen Handarbeit" (School of Feminine Handicrafts) and the "Kindergarten" of the reform educator Georgens.

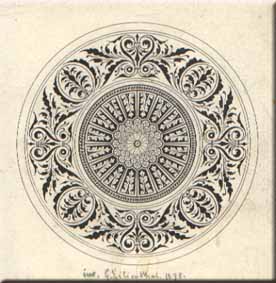

design by Gustav Lilienthal, 1878

design by Gustav Lilienthal, 1878

The term Arts and Crafts had at that time a more all-encompassing meaning than it possesses today. The term developed in the middle of the 19th century as a response to the conflict involving hand-made and mass-produced goods. It was a way of denigrating mass-produced goods as being of poor quality. Karl-Friedrich Schinkel wrote with his "Vorbilder für Fabrikanten und Architekten" (Prototypes for Manufacturers and Architects), a handicrafts pattern book, and Gotfried Semper wrote an influential analysis of the phenomena in "Wissenschaft, Industrie und Kunst" (Science, Industry and the Arts). The first german arts and crafts museum developed into a state-supported arts and crafts school. But these schools were reserved only for male students — just as earlier schools had been. An educational reform seemed overdue. Gustav obviously anticipated receiving state support for his school project.

During this time he also developed what later become known as "Anker-Steinbaukasten" (Anchor Stone Building Blocks). These toy blocks result from a synthesis of the three chief focusses of Gustav Lilienthal's activities: arts and crafts, architecture, and educational toys. Lilienthal felt that the "play" assignments of the educator Friedrich Fröbel should be combined with the use of stone building materials and realistic model architecture should be encouraged. Gustav felt the idea should not be limited to kindergarden playrooms, but applied to the building of architecture models as well. First there were several attempts to market the building blocks, but these met with little success. Gustav and his brother Otto — who was chiefly involved where manufacturing equipment and techniques were concerned — decided to sell them to interested clients. A buyer, Friedrich Adolf Richter from Rudolstadt, subsequently applied for his own patent for artificial sandstone. Richter transformed "his" discovery into the label "Anker" (Anchor), which became a successful product, exported to over 40 countries.

from a catalog of "Achor Stone Building Blocks"

from a catalog of "Achor Stone Building Blocks"

Since state support for his arts and crafts school didn't materialize, and since his toy building blocks were also not an economic success, Gustav planned to emigrate with his sister Marie to Brazil. But because of the situation in Brazil in 1880, suddenly Australia became their planned destination. Gustav would become a master-builder for the English civil service in Melbourne. Five years later he returned to Germany, while Marie remained in New Zealand until her death. One reason for Gustav's return was apparently his plan to again begin the production of his toy building blocks using a different material — that this time would be patented. On trips to Paris, Brussels and London Gustav Lilienthal began to build up a sales network. Also new ideas, including near-realistic roof tiles for the miniature houses, were brought to fruition. In an attempt to market the improved toy building block system, a legal battle with Richter ensued.

The laughable proceeds of the sale of the toy building blocks had made possible Gustav's steamer passage to Australia, and allowed Otto to earn barely enough to start his machine factory. Because of the lawsuit with Richter, the brother's second attempt to market the toy blocks didn't turn a profit. Gustav and Otto were only barely able to avoid total financial ruin. They were only able to pay a portion of legal costs and fines they had incurred losing the lawsuit by surrendering to Richter their new toy block manufacturing machinery, and by giving up their patent rights to the improvements they had made to the toy system. Gustav had to declare bankrutpcy and Otto's finances were hard hit.

Only much later would Gustav come to be recognized and appreciated as the actual inventor of the stone blocks. Since 1995, the manufacture of perfect reproductions of the building blocks has re-commenced in Rudolstadt according to the original specifications.

Castles and Barracks

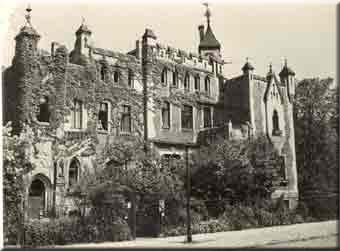

Lilienthal's surviving buildings are numerous and diverse. The best-known are the "Castles of Lichterfelde", approximately 30 suburban villas in the english tudor style, complete with battlements and towers. The homes in this Berlin suburb look as if they are enlarged versions of models designed using Anker toy building blocks. Those that have maintained their original style or have been restored are still eye-catching. Playful or even a bit 'overdone', would probably be one's initial judgement, but the external appearance obscures Lilienthal's actual aim.

Gustav Lilienthal's "castles", Berlin-Lichterfelde, Marthastraße 5

Gustav Lilienthal's "castles", Berlin-Lichterfelde, Marthastraße 5

"A suburban house for the family", whose vision is expressed in the Lichterfelde homes, is one of the few works of Lilienthal that doesn't have to do with flight technology. The houses are just the opposite of what they appear to be. They were designed to be highly utilitarian and were very economical in their construction. At the time, Lichterfelde lay at the edge of city development and still outside the city limits. Despite that, the parcels are tiny and every ornament serves a function. The chimneys and air shafts are concealed by turrets, and even the drawbridges accessing the entrances in front of some houses span moats that allow daylight into the basement-level bedrooms. "Wide-brimmed cornices or peaked roofs are luxuries which a bank will certainly allow. However, a country home constructed with close attention to costs can't be so profligately designed. One must therefore resort to other decorative devices", he explained in an article. His aim was to provide affordable housing for the "lower middle class." The first home to be built, a particularly small model, he moved into himself. His subsequent home in the Lichterfelde developement is still occupied by his granddaughter today.

What kind of prospects for a life beyond the "Mietskasernen" (renter's barracks) existed for those outside the middle classes? In a vegetarian restaurant in Berlin the "Eden" project was born on May 28, 1893, and the structure of the community as non-profit vegetarian fruit-growing cooperative sketched out. Three trees, arranged in a triangle, still form the logo of the cooperative. They symbolize reform of one's life, and economic reform based upon land reform. Communal land, self-marketing of the fruit, community-developed educational and cultural institutions, and the construction of individual "homesteads", this was the basis of the project. The new cooperative members lived first in the "Spatzenburg" (sparrow castle), the community accomodation for new "settlers", while they were building their own "homesteads."

Home in "Eden" built with hollow-core concrete blocks

Home in "Eden" built with hollow-core concrete blocks

Gustav Lilienthal developed a process for the manufacture of poured concrete blocks on-site with the help of the "settlers" themselves. He was architect and builder for the community buildings and numerous homes in the settlement, many of which are still to be seen in "Eden" today. Obviously the "Eden" project was an inspiration to Lilienthal for his own subsequent cooperative project, the "Freie Scholle" (Free Soil) cooperative, in this case located in northern Berlin. Here as well he developed a building design utilizing concrete blocks, which were manufactured on-site.

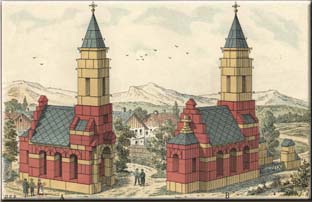

Stilll lower down the soclal ladder live the homeless and migrant laborers of Berlin. These "Brothers of the Highway" found shelter in the "Hoffnungstal and Lobetal Institute" (Hope Valley and Praise Valley), that was founded near Berlin by the theologian Friedrich von Bodelschwingh. When Bodelschwingh initially arrived Berlin as a Legislator, he was confronted with conditions among the hundreds of thousands of Berlin homeless people which were beneath human dignity. Today the "Saal Altlobetal" (Old Praise Valley Hall) is a landmark of the Institute. To our surprise, this building is also connected with Gustav Lilienthal. The former Lazarus Chapel, a half-timbered church on the Gubener Strasse in the vicinity of the Berlin Ostbahnhof, was dismantled and reconstructed in Lobethal in a modified form — to a large extent by the "colonists", under the direction of Gustav Lilienthal.

The first actually functional buildings in "Hope Valley" were sleeping dormitories. Bodelschwing's formula "working, not begging" envisioned each "colonist" being provided with a place to spend the night (a bed separated at least by screens, the so-called "Einzelstübchen" or private space). In exchange, they were obliged to perform some kind of labor the following day. A fellow Legistlator recommended Gustav Lilienthal to Bodelschwingh. "I doubt that anyone else can deliver the same quality of fire-proof and weather-proof barracks, which offer such spacious accomodation for 42 people, built for a price of 9,500 Reichsmarks ... Mr. Lilienthal, who has been well-known for many years for his lively interest in non-profit enterprises, sets for himself, and unfortunately also for his family, the smallest conceivable compensation requirements."

light-weight and pre-fabricated buildings, named "Terrast"

light-weight and pre-fabricated buildings, named "Terrast"

Lilienthal had developed a process for manufacturing transportable houses utilizing pre-cast concrete slabs. Under the name "Terrast-Baugesellschaft" (Terrast Construction Company), various prefabricated floor and wall elements, even for multi-story houses, were offered for sale. The houses in "Eden" and "Hope Valley" were promoted alongside other examples of the firm's products. "Detachable and tranportable homes, liveable in both summer and winter seasons" proclaimed the firm's letterhead. Lilienthal was prolific not just in the development of building block systems in miniature, but also in developing processes for light-weight and pre-fabricated construction.

These construction methods had a corresponding miniature as well: one of the patents cited was initially patented for the Lilienthal toy buildings, the pre-cursor of the "Meccano" or "Erector Set."

Gustav Lilienthal's "Modellbaukasten", (erector set), 1888, (museum's collection)

Gustav Lilienthal's "Modellbaukasten", (erector set), 1888, (museum's collection)

One can describe Lilienthal as a someone who paved the way for others with his innovations in the design of pre-fabricated building materials. But also in this, one of the most important areas of his professional activity, greater economic success eluded him. In 1912, at the age of 62, Lilienthal attempted once again to establish hiimself in Brazil with the help of his patented light-weight construction method. This attempt was also an economic failure.

But Lilienthal had already begun new investigations into bird flight. This would occupy a further 20 years of his life. His research concerning flapping wings and the utilization of naturally-occurring wind is extensive, but since the flapping wing has found no technical application up until now, his attempt will be judged by many as an misguided effort. Lilienthal made this opposite assessment about himself: "People in flight technology circles have called me a moth. I don't see that as a criticism. A person must be rather dense, when he or she can't gain inspiration from the marvelous ramifications of the simplest processes which reveal themselves in bird flight."

("Der geheimnisvolle Vorwärtszug" (The Mysterious Way Forward) in "Zeitschrift für Flugtechnik und Motorluftschiffahrt", 1913)